Historical Patterns of Conquest and Return in the Middle East

The narrative of colonization and decolonization has become central to contemporary geopolitical discourse, yet its application to Middle Eastern history reveals complex patterns that challenge simplified frameworks. Understanding the historical trajectory of Islamic expansion from Arabia through the Middle East and into Europe, contrasted with the Jewish return to their ancestral homeland, provides crucial context for modern debates about indigenous rights, territorial sovereignty, and cultural transformation.

The Great Expansion: Islam’s Territorial and Cultural Conquest (7th-8th Century)

Pre-Islamic Middle East: A Christian-Majority Region

Before the rise of Islam, the Middle East presented a dramatically different religious landscape. The Byzantine Empire controlled vast territories including Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt, where Christianity had flourished for centuries. Archaeological evidence and historical records demonstrate that cities like Damascus, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria served as major centers of Christian scholarship and worship.

Egypt’s Coptic Christian community represented the demographic majority, while Syria and Lebanon hosted thriving Christian populations of various denominations. Even Mesopotamia, under Persian Sassanid control, contained substantial Christian minorities alongside Zoroastrian populations.

The Islamic Conquest: Systematic Territorial Expansion

The death of Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE marked the beginning of one of history’s most rapid territorial expansions. Within a century, Arab armies had conquered territories spanning from Spain to Central Asia, fundamentally transforming the religious, cultural, and linguistic character of these regions.

Egypt (639-642 CE): Arab forces under Amr ibn al-As conquered Byzantine Egypt, ending over six centuries of Christian Byzantine rule. The conquest was swift, aided by Coptic Christian resentment toward Byzantine religious policies.

The Levant (634-638 CE): Damascus fell in 634, followed by Jerusalem in 638. These conquests eliminated Christian political control over Christianity’s birthplace and transformed the demographic trajectory of the region.

Theological Framework for Expansion: Islamic expansion operated under specific theological concepts, including the division of the world into dar al-Islam (the house of Islam) and dar al-harb (the house of war). The concept of jihad provided both spiritual and, in certain interpretations, military justification for territorial expansion.

Demographic and Cultural Transformation

The Islamic conquest initiated a centuries-long process of Arabization and Islamization. While initial Arab rule often maintained existing administrative structures and granted protected status (dhimmi) to Christians and Jews, economic incentives, social mobility opportunities, and cultural pressures gradually accelerated conversion.

Arabic became the administrative and scholarly language, displacing Greek, Coptic, and Aramaic. Urban centers converted more rapidly than rural areas, but over several centuries, formerly Christian-majority regions became predominantly Muslim.

Contemporary Demographics:

- Egypt: Approximately 10% Coptic Christian (down from pre-Islamic majority)

- Syria: Approximately 10% Christian (down from historical majority)

- Lebanon: Approximately 40% Christian (the highest remaining concentration)

The Jewish Experience: From Dispersion to Return

Historical Presence and Dispersion

Archaeological evidence confirms continuous Jewish presence in the land of Israel for over 3,000 years, despite various conquests and periods of displacement. The Roman destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE) and subsequent revolts led to significant Jewish dispersion, though communities remained throughout the Byzantine, Islamic, Crusader, Ottoman, and British periods.

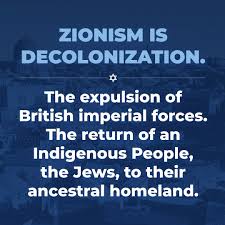

Unlike the Islamic expansion, which represented conquest of foreign territories, the modern Jewish return to Israel represents what can be understood as decolonization—the restoration of an indigenous people to their ancestral homeland after centuries of foreign rule.

Foreign Rule and Colonization of Jewish Homeland

The land that became modern Israel experienced successive waves of foreign conquest and control:

Islamic Period (638-1099, 1187-1517): Arab and later various Islamic dynasties ruled the region for roughly 850 years total.

Crusader Period (1099-1187): European Christian conquest and settlement.

Ottoman Period (1517-1917): Turkish Islamic rule for 400 years.

British Mandate (1917-1948): European colonial administration.

Throughout these periods, Jewish communities maintained presence and connection to the land, with periods of immigration and return occurring under various rulers.

Modern Decolonization: The Return Movement

The modern Zionist movement, beginning in the late 19th century, represented a decolonization effort—seeking to restore Jewish political sovereignty in their indigenous homeland. This movement gained international legal recognition through the Balfour Declaration (1917), League of Nations Mandate (1922), and ultimately UN Resolution 181 (1947).

The establishment of Israel in 1948 marked the end of nearly 1,900 years of foreign rule over the Jewish homeland and the restoration of Jewish self-determination.

Contemporary Parallels: Europe and Cultural Expansion

Modern Islamic Expansion in Europe

Contemporary Europe is witnessing demographic and cultural changes through immigration and higher birth rates among Muslim populations. While occurring through different mechanisms than historical conquest, the pattern raises questions about cultural transformation and integration.

Demographic Trends:

- France: 8-10% Muslim population

- Germany: ~6% Muslim population

- United Kingdom: ~6% Muslim population

Integration Challenges: Some European communities face tensions over secular governance versus religious law interpretations, educational curriculum, women’s rights, and freedom of expression—echoing historical patterns where expanding Islamic influence created cultural and legal conflicts with existing systems.

Analyzing the Frameworks

Colonization Patterns

Historical Islamic expansion demonstrated classic colonization characteristics:

- Military conquest of foreign territories

- Imposition of new legal, linguistic, and religious systems

- Gradual demographic transformation through conversion and immigration

- Political subordination of indigenous populations

- Economic systems favoring the conquering group

Decolonization Characteristics

The Jewish return to Israel exhibits decolonization features:

- Restoration of indigenous people to ancestral homeland

- End of foreign imperial rule

- Revival of ancient language and cultural practices

- International legal recognition of legitimate claims

- Resistance from recent settler populations and imperial powers

Implications for Contemporary Discourse

This historical analysis reveals the complexity of applying colonization/decolonization frameworks to Middle Eastern conflicts. While Islamic expansion transformed formerly Christian regions through conquest and gradual conversion, Jewish return to Israel represents the restoration of indigenous rights after centuries of foreign rule.

Understanding these patterns provides crucial context for evaluating contemporary claims about colonization, indigenous rights, and territorial sovereignty. It challenges narratives that ignore historical precedent and demographic transformation, while highlighting the importance of distinguishing between conquest and restoration in modern geopolitical analysis.

The ongoing debates about integration, cultural preservation, and religious accommodation in Europe echo historical tensions surrounding Islamic expansion, suggesting that these patterns continue to shape contemporary political and social dynamics across different geographical contexts.